Often depicted in movies and TV shows as ruthless, razor-toothed monsters, sharks long have been feared by humans. But thanks to the scientific research efforts undertaken by facilities like the Bimini Biological Field Station, nicknamed “Shark Lab,” in the Bahamas, the essential contribution sharks make to the planet is becoming better understood and appreciated. Sharks are apex predators that help to manage their prey species’ populations and, indirectly, that of their prey’s prey, ultimately impacting all parts of the food web and helping to preserve the balance and structure of the oceans’ ecosystems.

“The persona and perception of sharks has changed over time,” said Matt Smukall, Bimini Biological Field Station president, CEO and head of research. “We are one component of a larger group working to raise that awareness

Established in 1990 by Dr. Samuel Gruber on the small island of South Bimini, Shark Lab is dedicated to facilitating cutting-edge research into sharks and rays, known as elasmobranchs, along with educating future marine scientists and enhancing conservation awareness. Currently, eight students who are either in graduate school, college or are taking a gap year to improve their skills are in residence, supported by a staff of research technicians and interns.

Shark Lab also holds workshops for marine sciences educators from all over the United States, Canada and Europe. In addition, it has hosted more than 200 production companies making videos of sharks, rays and other aquatic species in the crystal-clear waters around Bimini. Shark Lab even has aided photography for several episodes of Discovery Channel’s famous “Shark Week” series.

“It is mostly entertainment, but you can sprinkle in a conservation message,” Smukall added.

The Shark Lab facility itself is designed to simulate an oceanographic research vessel on land, complete with a lab and living accommodations for up to 20 people. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when Shark Lab had to suspend research operations temporarily and send the students home, the resident staff undertook a major renovation that has greatly improved the facility. It still is not luxurious, but it puts the researchers within a short boat ride of the many fertile shark habitats and nurseries around North Bimini and South Bimini, including on the flats of the Great Bahama Bank and in the deep waters of the Gulf Stream between Bimini and Florida. In fact, a wet suit is just as essential as a laptop for most members of the Shark Lab team.

“Everything we do is in the water. You can teach people about marine ecosystems from a book, but you really need to get them out under the water,” Smukall said.

Research projects underway at Shark Lab include studies of tiger sharks, hammerhead sharks, bull sharks and lemon sharks, among other species. While the focus of each project varies from genetics to life cycle to behavior and more, sharks’ migratory habits are an important field of research.

“Sharks don’t know that there are international boundaries,” Smukall said. “We want to find out where they move, and why they move.”

To facilitate tracking their subjects, Shark Lab scientists and staff use boats to locate, catch, tag and release sharks in the waters around Bimini. The sophisticated tags they use include acoustic tags that use acoustic telemetry to transmit the shark’s location, and fin-mounted satellite transmitters, which send the tracking information to the facility via satellite transmission.

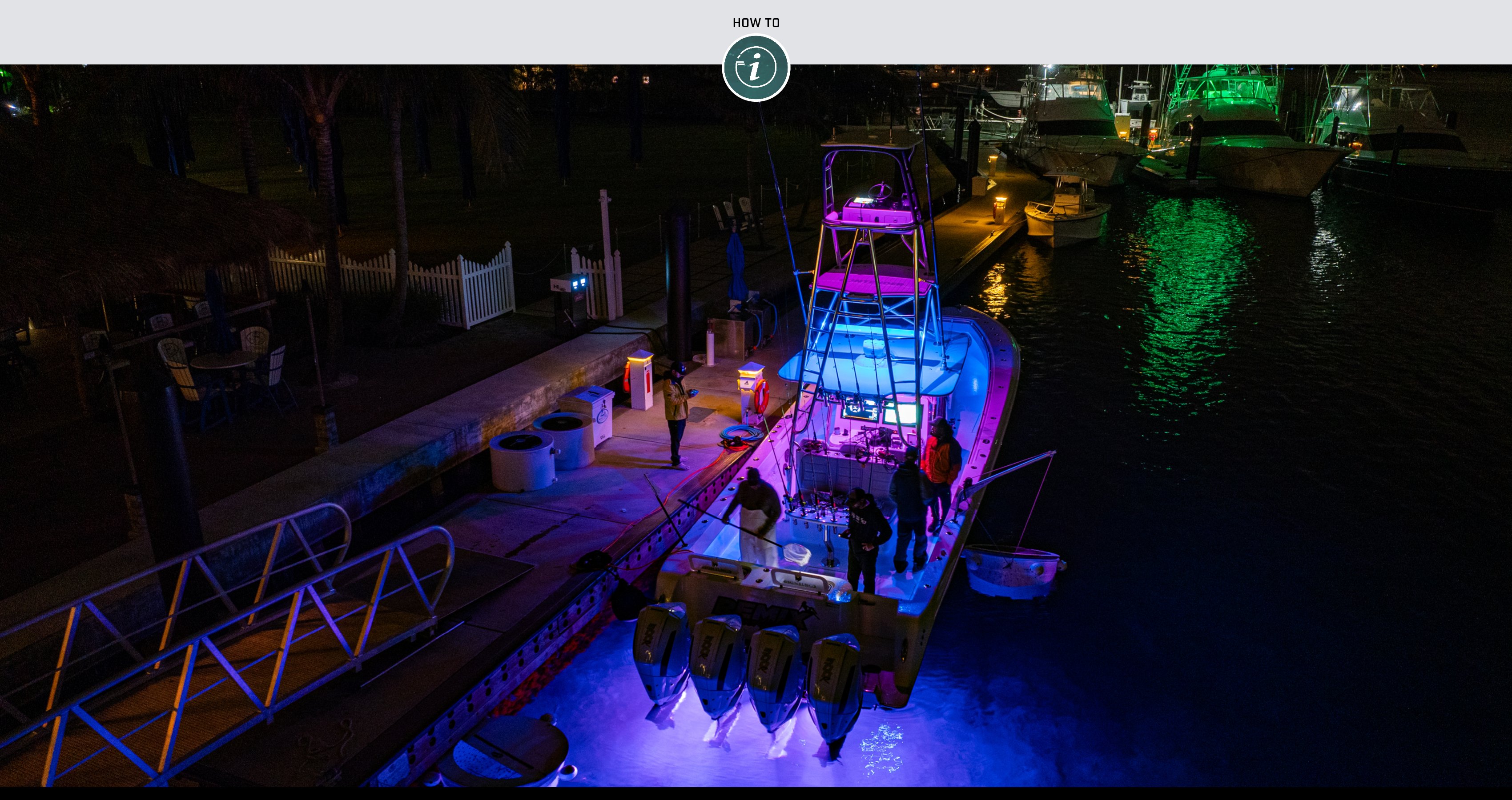

Mercury Marine has supported Shark Lab for many years by designating it as a Mercury-sponsored research facility. Today, the Shark Lab team has a fleet of 11 boats, including an assortment of skiffs and center-consoles, all powered by Mercury outboards ranging from 40 to 150hp.

“We average 500 hours a year per engine,” Smukall said.

Reliable, durable and user-friendly Mercury engines are crucial equipment for Shark Lab, because there are no boat-repair yards on South Bimini. If an engine were to break down on one of its boats, the staff would have to tow the boat 50 miles across the Gulf Stream to South Florida to have it repaired.

“Being on a remote island, you really have to have reliable engines,” Smukall said, adding, “When they do need maintenance, it’s pretty easy to do it ourselves.”

Not only is Shark Lab helping to expand shark science and increase awareness of the need for marine conservation, but Smukall and his team also are proud of the fact that the lab is helping to educate future instructors and, through them, future scientists.

“We appreciate being able to teach the next generation of faculty skills that they will bring with them when they move on to NOAA or to a university, and then spread those skills and that awareness,” he said.

For more information on the Bimini Biological Field Station and the research projects underway at the facility, visit biminisharklab.com.

Get a peek of a Shark Lab vessel in action by clicking here.